Scientists Create A Google Maps Of The Roman Empire–Plan Your Trip Along Their Famous Roads

It was said that all roads lead to Rome, but from where do all the roads to Rome lead?

Using a mountain of data, a team of two dozen scientists have created a digital road atlas of the Roman imperial world, complete with many features you’d recognize from Google Maps.

Called Itiner-e, it displays the roads that would have been found throughout the Roman Empire around the year 150 CE. It’s the most expansive research project on the topic to date, and increases the estimated length of the empire’s road system by over 60,000 miles.

At its height in the second century CE, the Roman Empire included over 55 million people and stretched as far north as modern day Britain to as far south as Morocco, eastward to the Syrian deserts, and, turning towards Europe, included all of Turkey, northeastern Bulgaria, and the Danube. It was carved up and maintained by a network of stone/gravel/sand highways stretching 117,162 miles.

But the total extent of the Roman interstate system had remained incompletely mapped and existing digitizations were low resolution. Seeking to improve on them, a vast international and interdisciplinary team of scientists from across Europe created Itiner-e using archaeological and historical records, topographic maps, and satellite imagery.

The dataset increases the known road converge to 180,000 miles across over 1 million square miles, mainly from new mapping across the Iberian Peninsula, Greece, and North Africa.

Their work also adapted previously-proposed road routes to fit geographical realities. This includes allowing roads crossing mountains to follow winding paths, as they likely would have, rather than direct lines.

It was estimated that around a third of the road system was highways, while two thirds would today be called B roads or secondary roads. The authors report that the precise locations of only 2.7% of the roads are known with certainty, while 89.8% are less precisely known, and 7.4% are hypothesized.

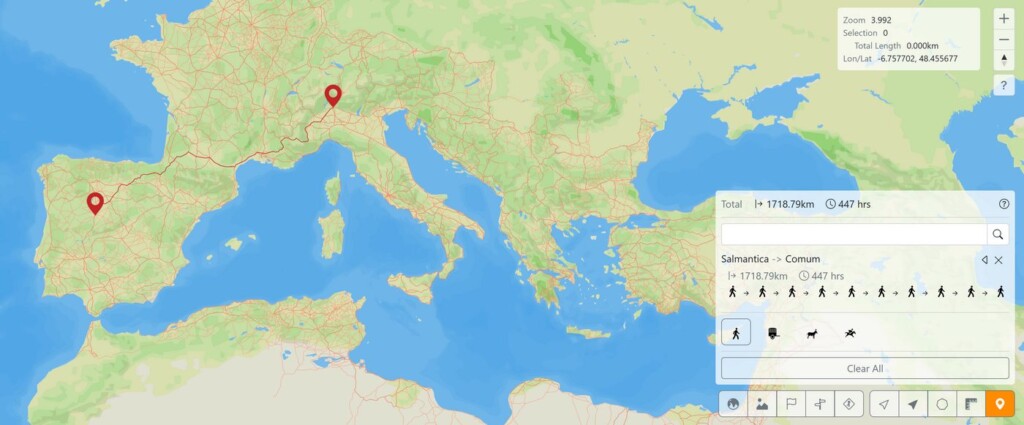

Using Itiner-e, a trip from the Spanish-Roman city of Salmantica (Salamanca) to near Comum, the city closest to the Italian home of GNN’s Managing Editor Andy Corbley, would have taken some 447 hours on Roman roads. Such a traveler could, however, be expected to make 2.4 miles per hour on foot because of the fine condition of the roads.

According to Itiner-e, one would take a Roman highway northeast to Pompelo (Pamplona) and continue on up over the Pyrenees, before turning off onto a secondary road towards Elusa in southern France. From there, the traveler would rejoin the highway running due east past Tolosa (Toulouse) and along the Cote d’Azur past Nemauses, (Nimes).

Secondary roads would take the traveler over and down the French Alps to Cuneo and then to Augusta Taurinorum (Turin) where there was a straight shot to Novaria (Novara). A secondary road would take the traveler north to the crossing of the River Ticino, where he would then leave the road to Comum via an undocumented Roman track that would see the weary wanderer home at last to Vergiate.

MORE ROMAN STORIES: Spy Satellite Photos Reveal Hundreds of Long-Lost Roman Forts, Challenging Decades-Old Theory

The road system was extremely sophisticated, allowing parts of it to last to our present time because of the many layers used to construct them. The goal was to build them so as to require as little maintenance as possible.

Typically a flat trench called a fossa would be dug down to the bedrock or firmest ground that was available. Fill, such as rubble or gravel, was then poured in until it filled the cracks in the bedrock and created a level surface. It would then be filled with native soil and then sand, if it were available.

DIGITAL ATLAS PROJECTS: Watch How Continents Moved Over 100 Million Years in Video – Mapped by Scientists as Never Before

Once the filling reached 1 yard of the surface, a layer of gravel would be tamped down, and a concrete-lime filling would follow, into which the Romans would stack stones as if the road were a wall, seeking the best and most natural fit between each stone to allow as little water and seed infiltration past the concrete. The road would be built in a slight arch to allow for quick drainage, just like modern motorways.

Sometimes, like in the Roman colonial city in Algeria, called Timgad, the roads had two lanes, also just like ours do today, (they drove on the right). A kind of mile marker and road sign would also be found, especially on the secondary roads.

WATCH a video production on the scope of the road system…

Please be good and do not spam. Thank you.