Gombe Stream Research Center at 65: How 65 Years of Chimpanzee Research Changed Science, Conservation, and Our Understanding of Ourselves

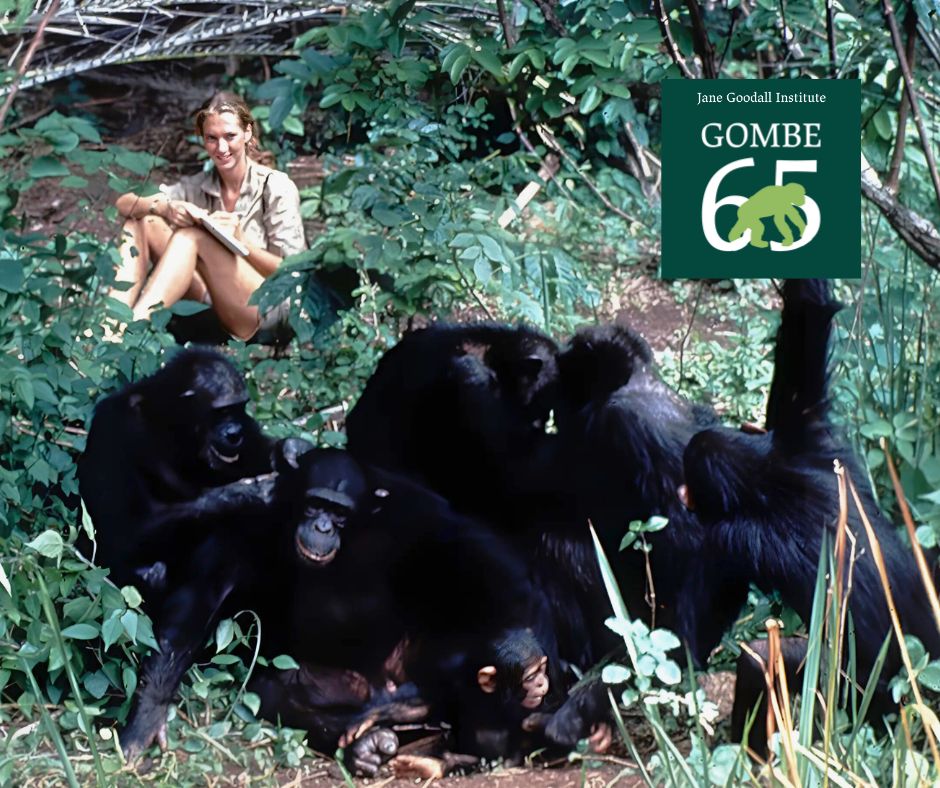

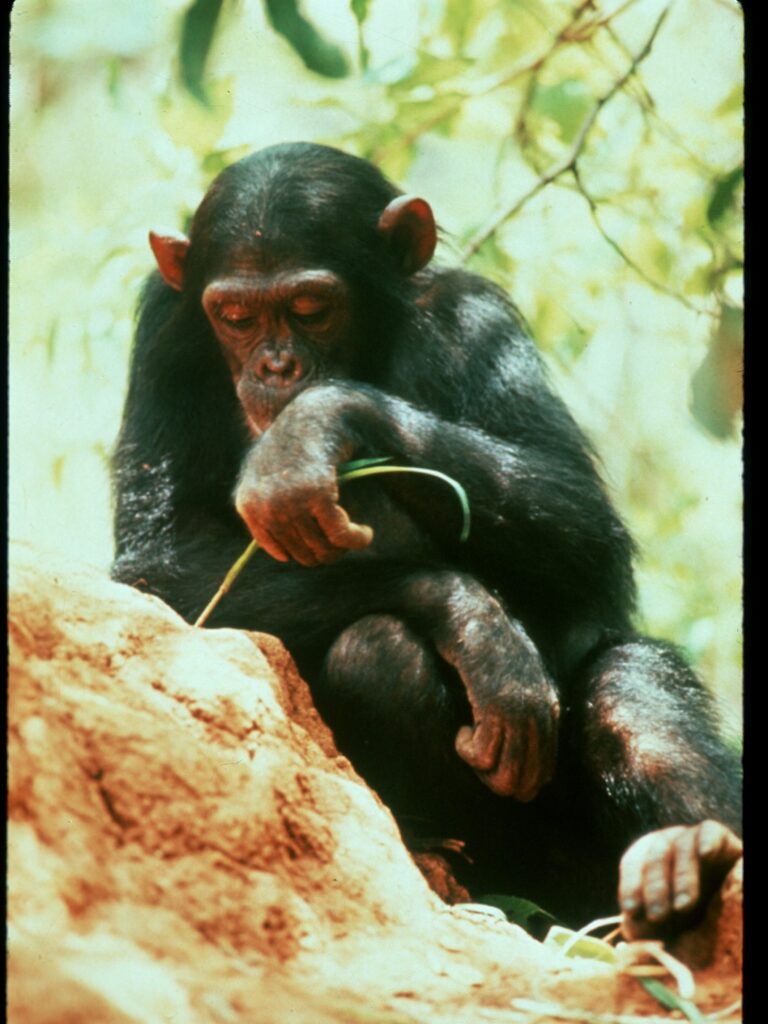

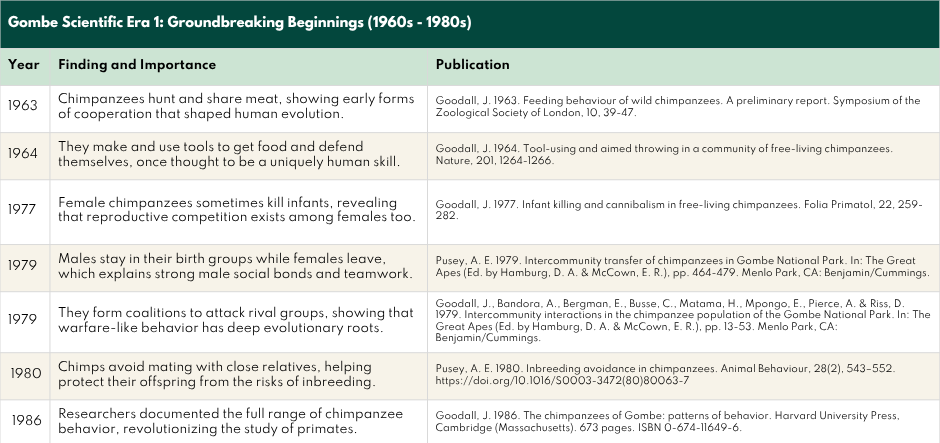

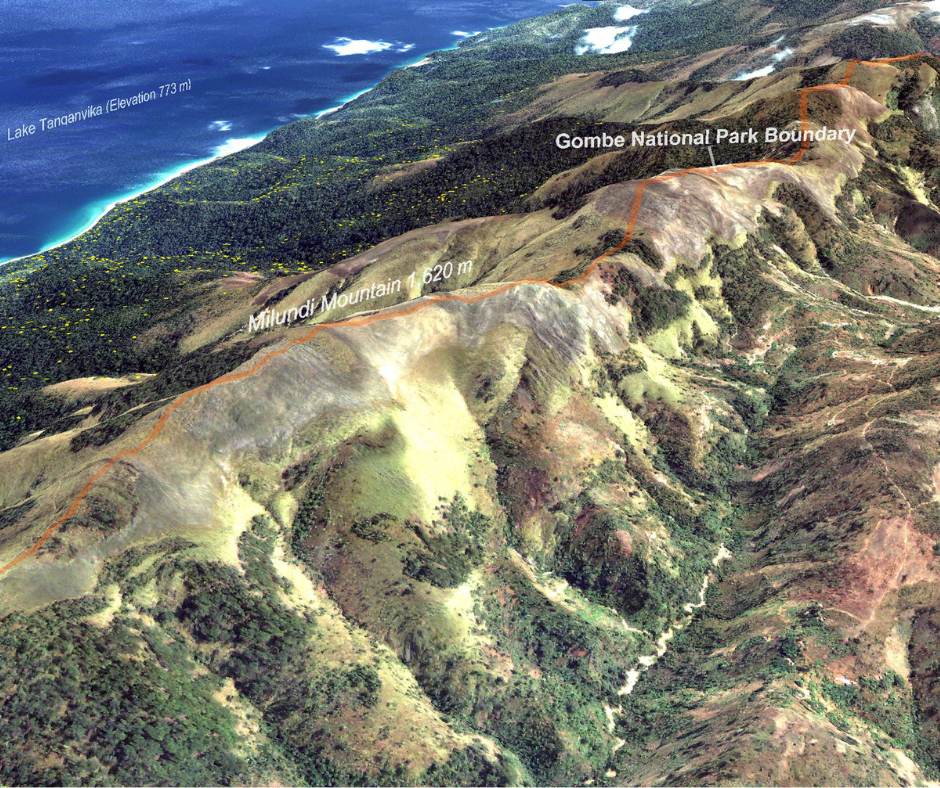

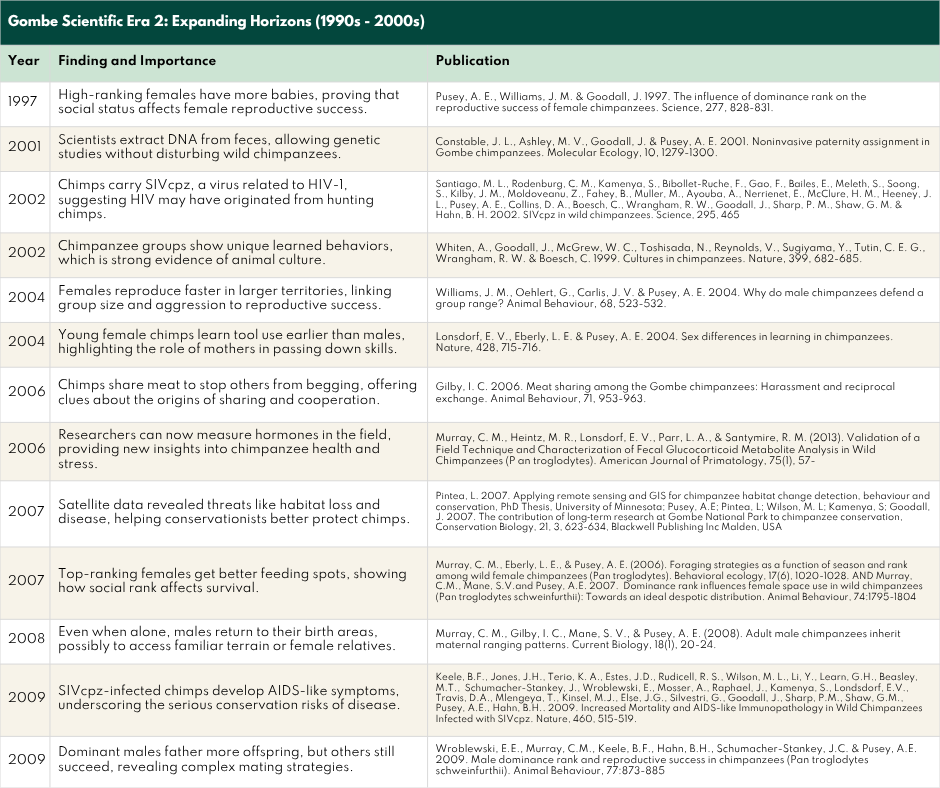

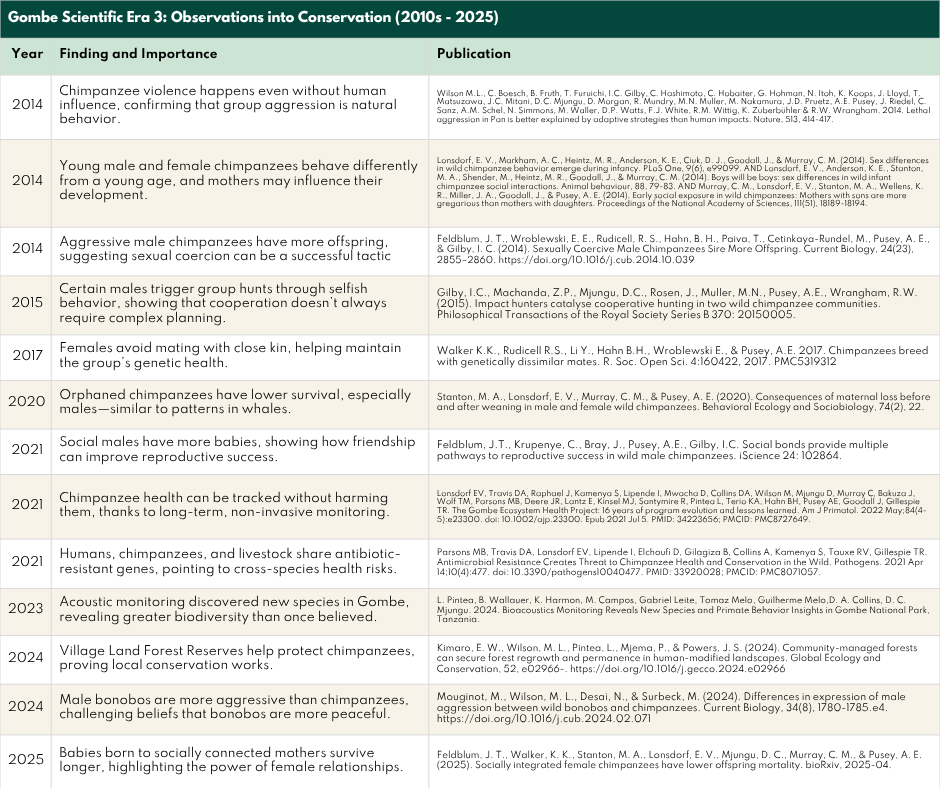

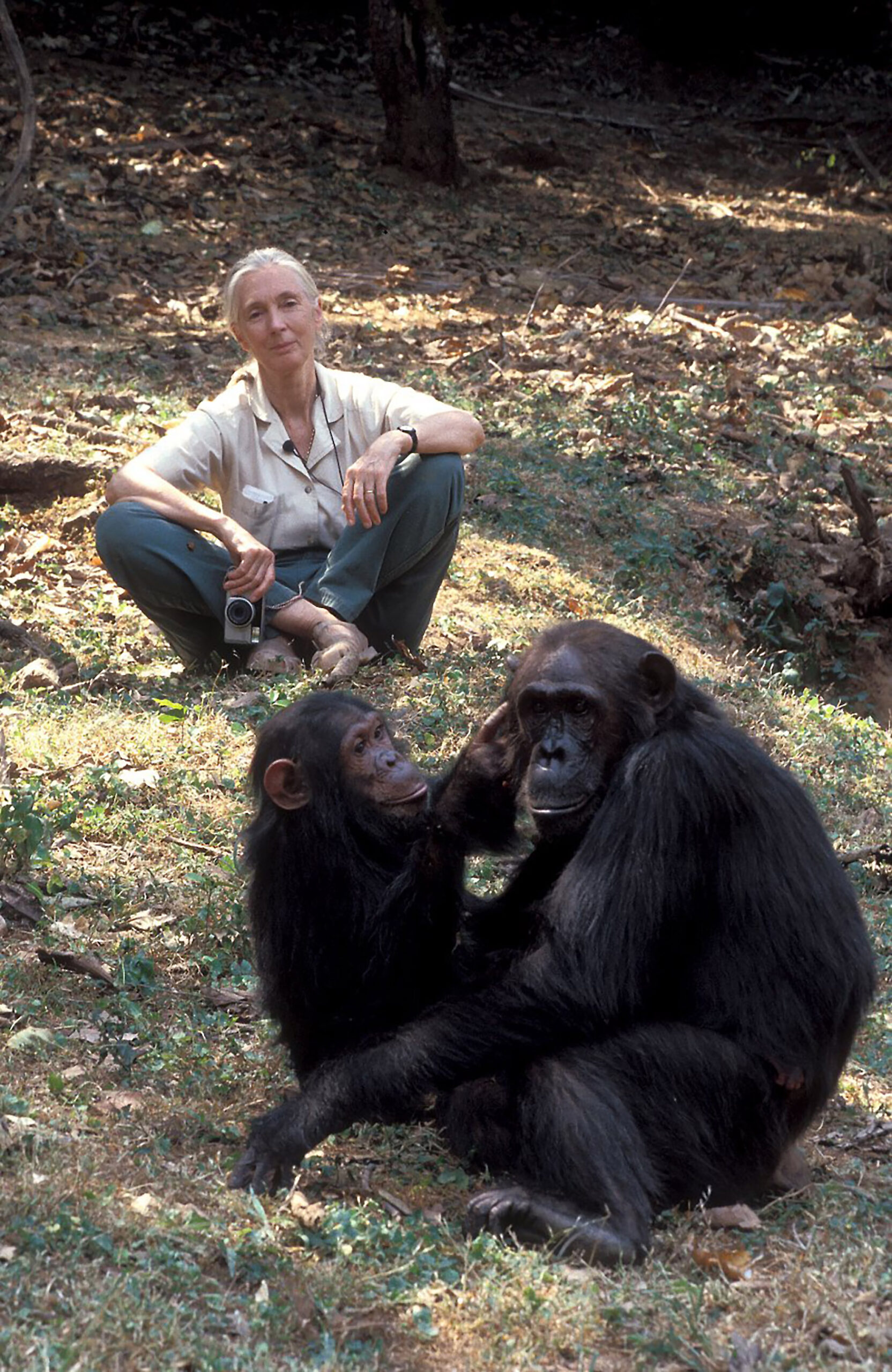

Every World Chimpanzee Day on July 14, we celebrate not only our closest living relatives in the animal kingdom—but also one of the most important places in the history of science and conservation: JGI’s Gombe Stream Research Center in Tanzania. This year marks 65 years of continuous research at Gombe Stream Research Center—the world’s longest-running wild chimpanzee study, driving groundbreaking discoveries in primatology, chimpanzee behavior, and wildlife conservation. It all began in 1960 when a 26-year-old Jane Goodall arrived in what is now Gombe, Tanzania. What began with a young woman and a notebook has evolved into one of the world’s longest-running, technology-driven wildlife studies—reshaping how we understand chimpanzees and other primates, the natural world, and what it means to be human. Now, 65 years later, Gombe’s story continues to unfold—a journey of curiosity, persistence, and innovation. With over 165,000 hours of behavioral data collected by more than 200 researchers and field assistants, Gombe has helped uncover insights on everything from chimpanzee community health monitoring to ecosystem biodiversity. To mark this milestone anniversary, we’re looking back at three defining scientific eras, each building on the last and revealing the complexity of our closest living relatives: the wild, intelligent, and deeply social chimpanzees. *Note on dates: Throughout this blog, all research will be referenced by its publication date, which may not reflect the exact year the behavior was first observed in the field. This era revealed chimpanzees as toolmakers, hunters, meat sharers, and even warriors—behaviors that, at the time, were believed to be uniquely human. Jane Goodall’s early field observations upended these assumptions. In 1960, she witnessed chimpanzees stripping leaves from twigs to fish for termites, a landmark discovery that marked the first recorded instance of non-human tool use in the wild (Goodall, 1964). Later, she documented chimpanzees hunting colobus monkeys and sharing meat with one another—suggesting complex cooperation and social reciprocity (Goodall, 1986). These findings painted a far more nuanced picture of chimpanzee societies—capable of deep bonds, collaboration, and conflict. Long-term studies also reshaped our understanding of gender roles in animal societies. Male chimpanzees were found to stay in their birth groups while females dispersed—a pattern known as male philopatry (Pusey, 1979). Even more surprising was the discovery of female-led infanticide (Pusey et al., 2008), revealing darker complexities in chimpanzee society. Together, these discoveries redefined our understanding of what it means to be human—and showed just how rich, complex, and sometimes uncomfortable the realities of chimpanzee life can be. Research highlight: Jane’s early observations and subsequent research from Gombe scientists revealed that chimpanzees hunt, share meat, use tools, and pass down local traditions — discoveries that helped launch modern field primatology and reshaped how we understand apes and ourselves. As new technologies emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s, JGI researchers began asking deeper questions and developing new, safer methods of data collection. By 2001, genetic analysis using fecal samples (Morin et al., 2001) allowed scientists to examine genetic markers—such as those indicating parent-offspring or sibling relationships—and trace kinship among chimpanzees. This kind of analysis revealed surprising divisions between communities that aren’t apparent through behavioral observation alone—and significantly, these insights emerged without interfering with the chimpanzees’ natural behavior. Around the same time, advances in virology led to one of the most globally significant discoveries: the identification of SIVcpz—the simian virus most closely related to HIV-1 (Keele et al., 2006). This finding established a direct link between chimpanzee health and human pandemics, expanding the relevance of Gombe research far beyond primatology and wildlife behavior. Meanwhile, long-term behavioral studies continued to challenge and refine our understanding of chimpanzee social dynamics. Researchers found that dominant females had greater reproductive success (Pusey et al., 1997), that tool learning begins earlier in females (Lonsdorf et al., 2004), and that males who shared meat experienced less harassment (Gilby, 2006). These insights deepened our understanding of the complex social lives and developmental differences within chimpanzee communities. By the 2000s, researchers were also looking outward—using satellite imagery to monitor environmental changes around Gombe. Remote sensing data (Wilson et al., 2007) revealed alarming trends in habitat loss and disease spread, placing chimpanzee survival within a broader conservation and landscape context. Research highlight: Noninvasive DNA and hormone collection revolutionized field biology, allowing scientists to measure kinship, stress and disease risk – all while preserving the wild nature of the chimpanzees they studied. This most recent era of Gombe research—spanning from the 2010s to today—has been marked by an integrated approach that combines behavioral observation, genetic data, and long-term monitoring to inform broader conservation strategies. By connecting how chimpanzees live, interact, and reproduce with the broader challenges they face, researchers are uncovering what it truly takes to support their survival in the wild. For example, studies revealed that while high-ranking males father more offspring, lower-ranking males also succeed through persistence and strategic social bonds (Wroblewski et al., 2009), demonstrating that there is more than one path to reproductive success. Sexual coercion was shown to give aggressive males a reproductive edge (Feldblum et al., 2014), while females actively avoided inbreeding by steering clear of close relatives (Walker et al., 2017), showing a sophisticated level of reproductive decision-making. One of the most critical findings of this era came from a landmark 2014 study (Wilson et al.), which provided definitive evidence that chimpanzees engage in organized intergroup conflict. This behavior had long been observed in Gombe, but some critics argued it might be a result of human disturbance. The 2014 study debunked that idea by documenting similar patterns across multiple chimpanzee communities, firmly establishing intergroup aggression as a natural part of chimpanzee social life. By understanding the complex interplay of genetics, behavior, and social structure, conservationists are better equipped to design strategies that ensure the survival of not just individual chimpanzees, but the integrity of their communities, social bonds, and culture. Research highlight: Gombe’s long-term lens showed us the complexity of survival – that evolution is not just about dominance but also about cooperation, strategy and adaptation to a changing world. For 65 years, the forests of Gombe have buzzed with discovery. From Jane’s first observations that shattered our assumptions about what it means to be human, to the ever-evolving science that connects behavior, health, genetics, and conservation—each era has deepened our understanding of our own human nature, the lives of chimpanzees, and the other abundant species who call Gombe home. Behind every breakthrough are the passionate researchers and field teams who ask bold questions and listen closely to the answers nature provides. As we celebrate this milestone, we invite you to meet some of these remarkable individuals in our upcoming “Voices from Gombe” blog, and to support JGI’s work as a Gombe Science Hero, or contribute directly to JGI’s mission. Right now, your donation can have double the impact thanks to our special matching campaign—every gift you make will be matched dollar-for-dollar, helping to advance vital research and conservation efforts. Because the story of Gombe is still being written—and we can’t wait to see what the next chapter holds. 🔗Learn more about becoming a Gombe Science Hero. 🔗Make a tax-deductible gift to JGI.

In this article (click to jump to a section):

Although Dr. Jane Goodall first observed many of these groundbreaking chimpanzee behaviors as early as 1960, as is typical in science, it often takes years of careful study, data collection, and peer review before findings are officially published in scientific journals. So while some of these behaviors—like tool use or meat sharing—were seen early on, the papers detailing them came out later.

Gombe Scientific Era 1: Groundbreaking Beginnings (1960s–1980s) — Tools, Hunting, and Social Discovery

Gombe Scientific Era 2: Expanding Horizons (1990s–2000s) — DNA, Disease, and New Technology

Gombe Scientific Era 3: Observations into Conservation (2010s–2025) — Conflict, Conservation, Community Insights

The Future of Gombe Stream Research Center: Continuing Legacy in Primate Research and Conservation

Select Publications from Gombe

Year Findings and Importance Publication 1963 Chimpanzees hunt and share meat, showing early forms of cooperation that shaped human evolution. Goodall, J. 1963. Feeding behaviour of wild chimpanzees. A preliminary report. Symposium of the Zoological Society of London, 10, 39-47. 1964 They make and use tools to get food and defend themselves, once thought to be a uniquely human skill. Goodall, J. 1964. Tool-using and aimed throwing in a community of free-living chimpanzees. Nature, 201, 1264-1266. 1977 Female chimpanzees sometimes kill infants, revealing that reproductive competition exists among females too. Goodall, J. 1977. Infant killing and cannibalism in free-living chimpanzees. Folia Primatol, 22, 259-282. 1979 Males stay in their birth groups while females leave, which explains strong male social bonds and teamwork. Pusey, A. E. 1979. Intercommunity transfer of chimpanzees in Gombe National Park. In: The Great Apes (Ed. by Hamburg, D. A. & McCown, E. R.), pp. 464-479. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings. 1979 They form coalitions to attack rival groups, showing that warfare-like behavior has deep evolutionary roots. Goodall, J., Bandora, A., Bergman, E., Busse, C., Matama, H., Mpongo, E., Pierce, A. & Riss, D. 1979. Intercommunity interactions in the chimpanzee population of the Gombe National Park. In: The Great Apes (Ed. by Hamburg, D. A. & McCown, E. R.), pp. 13-53. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings. 1980 Chimps avoid mating with close relatives, helping protect their offspring from the risks of inbreeding. Pusey, A. E. (1980). Inbreeding avoidance in chimpanzees. Animal Behaviour, 28(2), 543–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-3472(80)80063-7 1986 Researchers documented the full range of chimpanzee behavior, revolutionizing the study of primates. Goodall, J. 1986. The chimpanzees of Gombe: patterns of behavior. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts). 673 pages. ISBN 0-674-11649-6. 1997 High-ranking females have more babies, proving that social status affects female reproductive success. Pusey, A. E., Williams, J. M. & Goodall, J. 1997. The influence of dominance rank on the reproductive success of female chimpanzees. Science, 277, 828-831. 2001 Scientists extract DNA from feces, allowing genetic studies without disturbing wild chimpanzees. Constable, J. L., Ashley, M. V., Goodall, J. & Pusey, A. E. 2001. Noninvasive paternity assignment in Gombe chimpanzees. Molecular Ecology, 10, 1279-1300. 2002 Chimps carry SIVcpz, a virus related to HIV-1, suggesting HIV may have originated from hunting chimps. Santiago, M. L., Rodenburg, C. M., Kamenya, S., Bibollet-Ruche, F., Gao, F., Bailes, E., Meleth, S., Soong, S., Kilby, J. M., Moldoveanu, Z., Fahey, B., Muller, M., Ayouba, A., Nerrienet, E., McClure, H. M., Heeney, J. L., Pusey, A. E., Collins, D. A., Boesch, C., Wrangham, R. W., Goodall, J., Sharp, P. M., Shaw, G. M. & Hahn, B. H. 2002. SIVcpz in wild chimpanzees. Science, 295, 465 2002 Chimpanzee groups show unique learned behaviors, which is strong evidence of animal culture. Whiten, A., Goodall, J., McGrew, W. C., Toshisada, N., Reynolds, V., Sugiyama, Y., Tutin, C. E. G., Wrangham, R. W. & Boesch, C. 1999. Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature, 399, 682-685. 2004 Females reproduce faster in larger territories, linking group size and aggression to reproductive success. Williams, J. M., Oehlert, G., Carlis, J. V. & Pusey, A. E. 2004. Why do male chimpanzees defend a group range? Animal Behaviour, 68, 523-532. 2004 Young female chimps learn tool use earlier than males, highlighting the role of mothers in passing down skills. Lonsdorf, E. V., Eberly, L. E. & Pusey, A. E. 2004. Sex differences in learning in chimpanzees. Nature, 428, 715-716. 2006 Chimps share meat to stop others from begging, offering clues about the origins of sharing and cooperation. Gilby, I. C. 2006. Meat sharing among the Gombe chimpanzees: Harassment and reciprocal exchange. Animal Behaviour, 71, 953-963. 2006 Researchers can now measure hormones in the field, providing new insights into chimpanzee health and stress. Murray, C. M., Heintz, M. R., Lonsdorf, E. V., Parr, L. A., & Santymire, R. M. (2013). Validation of a Field Technique and Characterization of Fecal Glucocorticoid Metabolite Analysis in Wild Chimpanzees (P an troglodytes). American Journal of Primatology, 75(1), 57- 2007 Satellite data revealed threats like habitat loss and disease, helping conservationists better protect chimps. Pintea, L. 2007. Applying remote sensing and GIS for chimpanzee habitat change detection, behaviour and conservation, PhD Thesis, University of Minnesota; Pusey, A.E; Pintea, L; Wilson, M. L; Kamenya, S; Goodall, J. 2007. The contribution of long‐term research at Gombe National Park to chimpanzee conservation, Conservation Biology, 21, 3, 623-634, Blackwell Publishing Inc Malden, USA 2007 Top-ranking females get better feeding spots, showing how social rank affects survival. Murray, C. M., Eberly, L. E., & Pusey, A. E. (2006). Foraging strategies as a function of season and rank among wild female chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Behavioral ecology, 17(6), 1020-1028. AND Murray, C.M., Mane, S.V.and Pusey, A.E. 2007. Dominance rank influences female space use in wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii): Towards an ideal despotic distribution. Animal Behaviour, 74:1795-1804 2008 Even when alone, males return to their birth areas, possibly to access familiar terrain or female relatives. Murray, C. M., Gilby, I. C., Mane, S. V., & Pusey, A. E. (2008). Adult male chimpanzees inherit maternal ranging patterns. Current Biology, 18(1), 20-24. 2009 SIVcpz-infected chimps develop AIDS-like symptoms, underscoring the serious conservation risks of disease. Keele, B.F., Jones, J.H., Terio, K. A., Estes, J.D., Rudicell, R. S., Wilson, M. L., Li, Y., Learn, G.H., Beasley, M.T., Schumacher-Stankey, J., Wroblewski, E., Mosser, A., Raphael, J., Kamenya, S., Londsdorf, E.V., Travis, D.A., Mlengeya, T., Kinsel, M.J., Else, J.G., Silvestri, G., Goodall, J., Sharp, P.M., Shaw, G.M., Pusey, A.E., Hahn, B.H.. 2009. Increased Mortality and AIDS-like Immunopathology in Wild Chimpanzees Infected with SIVcpz. Nature, 460, 515-519. 2009 Dominant males father more offspring, but others still succeed, revealing complex mating strategies. Wroblewski, E.E., Murray, C.M., Keele, B.F., Hahn, B.H., Schumacher-Stankey, J.C. & Pusey, A.E. 2009. Male dominance rank and reproductive success in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii). Animal Behaviour, 77:873-885 2014 Chimpanzee violence happens even without human influence, confirming that group aggression is natural behavior. Wilson M.L., C. Boesch, B. Fruth, T. Furuichi, I.C. Gilby, C. Hashimoto, C. Hobaiter, G. Hohman, N. Itoh, K. Koops, J. Lloyd, T. Matsuzawa, J.C. Mitani, D.C. Mjungu, D. Morgan, R. Mundry, M.N. Muller, M. Nakamura, J.D. Pruetz, A.E. Pusey, J. Riedel, C. Sanz, A.M. Schel, N. Simmons, M. Waller, D.P. Watts, F.J. White, R.M. Wittig, K. Zuberbühler & R.W. Wrangham. 2014. Lethal aggression in Pan is better explained by adaptive strategies than human impacts. Nature, 513, 414-417. 2014 Boys and girls behave differently from a young age, and mothers may influence their development. Lonsdorf, E. V., Markham, A. C., Heintz, M. R., Anderson, K. E., Ciuk, D. J., Goodall, J., & Murray, C. M. (2014). Sex differences in wild chimpanzee behavior emerge during infancy. PLoS One, 9(6), e99099. AND Lonsdorf, E. V., Anderson, K. E., Stanton, M. A., Shender, M., Heintz, M. R., Goodall, J., & Murray, C. M. (2014). Boys will be boys: sex differences in wild infant chimpanzee social interactions. Animal behaviour, 88, 79-83. AND Murray, C. M., Lonsdorf, E. V., Stanton, M. A., Wellens, K. R., Miller, J. A., Goodall, J., & Pusey, A. E. (2014). Early social exposure in wild chimpanzees: Mothers with sons are more gregarious than mothers with daughters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(51), 18189-18194. 2014 Aggressive males have more offspring, suggesting sexual coercion can be a successful (but troubling) tactic. Feldblum, J. T., Wroblewski, E. E., Rudicell, R. S., Hahn, B. H., Paiva, T., Cetinkaya-Rundel, M., Pusey, A. E., & Gilby, I. C. (2014). Sexually Coercive Male Chimpanzees Sire More Offspring. Current Biology, 24(23), 2855–2860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.10.039 2015 Certain males trigger group hunts through selfish behavior, showing that cooperation doesn’t always require complex planning. Gilby, I.C., Machanda, Z.P., Mjungu, D.C., Rosen, J., Muller, M.N., Pusey, A.E., Wrangham, R.W. (2015). Impact hunters catalyse cooperative hunting in two wild chimpanzee communities. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society Series B 370: 20150005. 2017 Females avoid mating with close kin, helping maintain the group’s genetic health. Walker K.K., Rudicell R.S., Li Y., Hahn B.H., Wroblewski E., & Pusey, A.E. 2017. Chimpanzees breed with genetically dissimilar mates. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4:160422, 2017. PMC5319312 2020 Orphaned chimpanzees have lower survival, especially males—similar to patterns in whales. Stanton, M. A., Lonsdorf, E. V., Murray, C. M., & Pusey, A. E. (2020). Consequences of maternal loss before and after weaning in male and female wild chimpanzees. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 74(2), 22. 2021 Social males have more babies, showing how friendship can improve reproductive success. Feldblum, J.T., Krupenye, C., Bray, J., Pusey, A.E., Gilby, I.C. Social bonds provide multiple pathways to reproductive success in wild male chimpanzees. iScience 24: 102864. 2021 Chimpanzee health can be tracked without harming them, thanks to long-term, non-invasive monitoring. Lonsdorf EV, Travis DA, Raphael J, Kamenya S, Lipende I, Mwacha D, Collins DA, Wilson M, Mjungu D, Murray C, Bakuza J, Wolf TM, Parsons MB, Deere JR, Lantz E, Kinsel MJ, Santymire R, Pintea L, Terio KA, Hahn BH, Pusey AE, Goodall J, Gillespie TR. The Gombe Ecosystem Health Project: 16 years of program evolution and lessons learned. Am J Primatol. 2022 May;84(4-5):e23300. doi: 10.1002/ajp.23300. Epub 2021 Jul 5. PMID: 34223656; PMCID: PMC8727649. 2021 Humans, chimpanzees, and livestock share antibiotic-resistant genes, pointing to cross-species health risks. Parsons MB, Travis DA, Lonsdorf EV, Lipende I, Elchoufi D, Gilagiza B, Collins A, Kamenya S, Tauxe RV, Gillespie TR. Antimicrobial Resistance Creates Threat to Chimpanzee Health and Conservation in the Wild. Pathogens. 2021 Apr 14;10(4):477. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10040477. PMID: 33920028; PMCID: PMC8071057. 2023 Acoustic monitoring discovered new species in Gombe, revealing greater biodiversity than once believed. L. Pintea, B. Wallauer, K. Harmon, M. Campos, Gabriel Leite, Tomaz Melo, Guilherme Melo,D. A. Collins, D. C. Mjungu. 2024. Bioacoustics Monitoring Reveals New Species and Primate Behavior Insights in Gombe National Park, Tanzania. 2024 Village Land Forest Reserves help protect chimpanzees, proving local conservation works. Kimaro, E. W., Wilson, M. L., Pintea, L., Mjema, P., & Powers, J. S. (2024). Community-managed forests can secure forest regrowth and permanence in human-modified landscapes. Global Ecology and Conservation, 52, e02966-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2024.e02966 2024 Male bonobos are more aggressive than chimpanzees, challenging assumptions that bonobos are always more peaceful. Mouginot, M., Wilson, M. L., Desai, N., & Surbeck, M. (2024). Differences in expression of male aggression between wild bonobos and chimpanzees. Current Biology, 34(8), 1780-1785.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2024.02.071 2025 Babies born to socially connected mothers survive longer, highlighting the power of female relationships in chimp society. Feldblum, J. T., Walker, K. K., Stanton, M. A., Lonsdorf, E. V., Mjungu, D. C., Murray, C. M., & Pusey, A. E. (2025). Socially integrated female chimpanzees have lower offspring mortality. bioRxiv, 2025-04.

Please be good and do not spam. Thank you.